QI 氣

In recent decades, the idea of qi (ch'i 氣) has forced its way into the West through the practice of Qi Gong (Ch'i kung) 氣功 in both healing techniques and martial arts. This social phenomenon in turn has arrested the curiosities of the academics as well as lay people. Owing to its autochthonous yet ambiguous nature, the early French sinologists Marcel Granet (1884–1940) and Henri Maspero (1883–1945) showed an intriguing reluctance to discuss qi. The later Anglo-Saxon sinologists Angus C. Graham (1919–1991) and Benjamin I. Schwartz (1916–1999) preferred to leave qi untranslated but suggested that qi is the closest Chinese approximation to the Western concept of “matter.” Qi, Graham writes, is “adapted to cosmology as the universal fluid, active as Yang and passive as Yin, out of which all things condense and into which they dissolve. But in its older sense, which remains the primary one, it is like such words in other cultures as Greek pneuma ‘wind, air, breath’. It is the energetic fluid which vitalizes the body, in particular as the breath, and which circulates outside us as the air.”[1]

With regard to the translation of qi into English as “matter,” Schwartz cites a passage from Tso-chuan《左傳》: in the perspective of a physician, qi in the human body can be “stopped up, become congested, and thus become reduced and attenuated.” He thus argues that qi “seems to refer to a sort of circulating fluidum that has the Cartesian attribute of matter as the spatially extended, and ch’i may certainly have properties which are in later Western thought attributed to matter.”[2]

It is also clear, however, that ch’i comes to embrace properties which we would call psychic, emotional, spiritual, numinous, and even “mystical.” It is precisely at this point that Western definitions of “matter” and the physical which systematically exclude these properties from their definition do not at all correspond to ch’i. There seems to be absolutely no dogma that these properties may not simultaneously inhere in the same “substance.” To the extent that the word “energy” is used in the West to apply exclusively to a force that relates only entities described in terms of physical mass, it is as misleading as matter, I think, as an over-all name for ch’i.[3]

Nonetheless, Schwartz makes an argument in the case of Thales and Anaximenes: “one can by no means dogmatically say that the ‘primordial stuff’ excludes the psychic, the spiritual, or the numinous any more than the dynamic. Anaximenes’s air, like Thales’s water, is ‘full of gods.’”[4] In the perspective of the primordial stuff (matter, air or breath) that is “full of gods,” the American-born and France-based sinologist John Lagerwey takes a further step and sheds light into a far vision. He remarks, “like the Hebrew ruah, ch’i means both ‘breath’ and ‘breath of life, spirit.’” However, qi, or the Chinese idea of “breath[,] is used not to speak but to write”[5] in contrast with the Western idea of breath which sees speech as breath. Speech—the voice and the phonetic—is identified as Creator, or Spirit. As the Bible says: “And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul” (Genesis 2:7; KJV). God created the world by breath and speech.

Lagerwey argues that the Chinese character was not made first for the purpose of recording speech but as a means to communicate with heaven, spirits, or gods. He suggests that Chinese writing possibly existed before linguistic articulation as imbricated talismanic graphs and is related to the idea of breath and spirit in China as much as in the Western tradition of voice side by side with breath and spirit. Lagerwey expounds on Derrida and offers a rather unique view:

As Jacques Derrida well demonstrated, our civilization of Writing in reality is a civilization of Speech. It is through using a phonetic writing that we have been led to see in writing a simple duplication of the “living voice”: speech—whether of man or God—has the power to create things, or to realize them; it alone can express the essence—the intention, the will—and it was thus naturally identified with what gives life, with the spirit, with the soul, and with the breath. “Writing,” writes Derrida, “the letter, the sensible inscription, has always been considered by Western tradition as the body and matter external to the spirit, to breath, to speech, and to the logos.” One could not, from this perspective, conceive of a writing that could be other than a notation of speech, which was even eternally anterior to speech.

This writing has always existed in China. And, surprisingly, it was as much related to the concept of breath as the idea that we have of speech. For Chinese, the relationship between speech and breath is natural. There is nothing more natural, indeed, than to unite in a single movement of thought the voice and the breath that carries it: speech is the breath that calls into existence, which names, forms, distinguishes—in a word, creates. The ultimate expression of this Western bias is the Name of God.

The Chinese case allows us to understand that this view is a reflection of our anthropocentrism: it is the use of human breath—to talk—which becomes the ontological model for the whole universe. In China, it is the breath that counts: in the tohu-bohu origin—the Chinese named it hun-tun, the humpty dumpty chaos—the breath flows, first formless, chaotic, after long gestation cycles, then takes shape, settles. The pure and light breath ascends to heaven, disordered and heavy breath descends to earth. Hence, the diverse universe—called Tiandi, “heaven and earth”—is in existence.[6]

As if the Chinese regard qi as an objectively cosmic entity, humans are grounded in the larger scheme. There is no Genesis or idea of creation or course of creation of the universe by a single God. The Chinese idea of qi is more of a “rational” or “scientific” idea. Like the Big Bang, all of a sudden everything happens and evolves, the lighter qi ascends as heaven and the heavy qi descends as earth. Thus there is tian di天地 “heaven and earth,” or universe. Tian, the heaven, is spoken of as father in a dual relationship with di, the earth, which plays the role of mother. Heaven and earth exist in the way of equilibrium (not domination), and then life begins. The essential relation of the Chinese heaven and earth is ganying感應, or “resonant,” via qi circulation amongst humans, events, nature, and heavenly bodies. In this cosmological order, space and time, things and events, tastes and colors, and so on and so forth belong to the same category and affect each other. This complex and systematic process is not mechanical causation but resonant response; for instance, the cardinal direction of west resonates with the season of autumn, the human emotions of sorrow and regret, the human organs and body parts of lungs, skin, and hair, and certain human behaviors and social activities at certain times. It is symbolic of weapons, war, death, and harvest, of fruitful conclusion, and so on. As Prince Huainan《淮南子》(compiled in 202 BCE) states, in autumn “the emperor wears a white outfit, offering animal livers to ancestors, riding a black-tailed white horse with a white flag, residing in the west palace, and he engages in war, hunting . . .”[7]

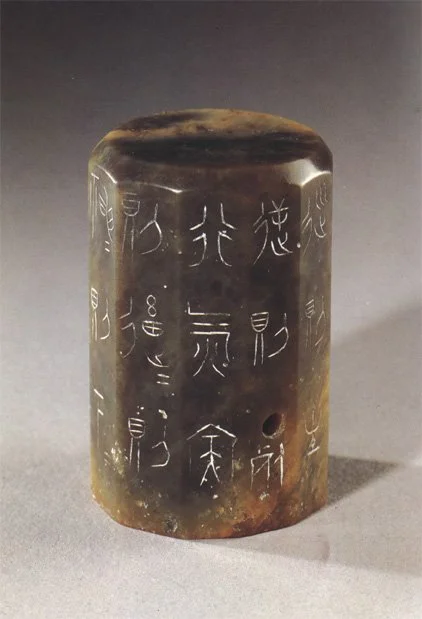

From the beginning Chinese writing consists of imbricated talismanic graphs, and thus is the character, the image, and the representation of the patterns of “heaven and earth.” The graph of qi appeared in jiagu 甲骨文 the oracle bone inscriptions, and in jinwen 金文 the bronze inscriptions, yet we have so far found no evidence that any concept of qi existed in the Shang (1766-1122 B.C.) or the early Zhou periods (1122-481 B.C.). However, the frequent usage of qi can be traced back to the Warring States Period (481-221 B.C.). In particular, the inscribed jade artifact “xinqiming 行氣銘 the Circulating Qi Inscription,” thought to be from the Warring States Period, confirms that the concept of qi and the practice of “qi circulation” took place in the early Warring States Period, if not earlier.

According to Shouwen《說文》,the early graph qi 气 depicted “cloud vapor” and is consistent with the form on the graph of the oracle bone and bronze inscriptions. While the more common graph 氣, also supported by Shouwen, emphasizes its rice component, the third graph found in the “Circulating Qi Inscription” has a fire component replacing the rice. Comparing the graphs, one’s view confirms Schwartz’s observation that qi “represents the nourishing vapors of boiling rice or grain. These vapors represent the nourishing powers of food that maintain life and human energy.”[8]

The rubbing of the inscribed jade artifact “Circulating Qi Inscription, or xinqiming 行氣銘” was dated as the first esoteric meditation text from the early Warring States Period (481-221 B.C.).

The graph that emphasizes the fire component, suggests Sarah Allan, is “a prototypical image of clouds produced by sun on water or else of steam, that is, water vaporized by fire. Nevertheless, the qi that is the primary subject of the inscription is the human breath.”[9] This “human breath,” or the qi graph with the added fire component, may be a suggestive link to the fourth qi graph 炁, which indicates the “configured breath” in the Taoist practice, such as the Inner Alchemy or neidan 內丹 exclusive to the literature and practices.

In spite of its esoteric nature, or rather, its trivial philosophical or literary significance—few Western scholars have yet treated the text of “Circulating Qi Inscription” (aside from Allan's quick review)—the dating of the “Circulating Qi Inscription” has been examined by a number of Chinese scholars. According to Li Ling's interpretation of the original text, the “Circulating Qi Inscription” corresponds to the “Rendu Micro-orbit Channeling Qi Gong 任督二脈小周天氣功.” The verse of “Circulating Qi Inscription” reads:

When one inhales (so that one) swallows (the qi), qi is gathered. As qi has gathered, it expands. As qi has expanded, it goes downward. As qi goes downward, it settles. As qi is settled, it solidifies. As qi is solidified, it sprouts. As qi sprouts, it grows. As qi grows, it is returned. As qi returns, it ascends to heaven. The origin of heaven is in the above, the origin of earth at the below. One follows (such way), one lives. One is against (such way), one dies.

行氣:吞則蓄,蓄則伸,伸則下,下則定,定則固,固則萌,萌則長,長則復,復則天。天其本在上,地其本在下。順則生,逆則死。[10]

Li Ling suggests that “the origin of heaven” is the upper dantian 上丹田 while “the origin of earth” is the lower dantian 下丹田. Accordingly, the “Circulating Qi Inscription” becomes the first complete esoteric text for “qi gong” practice. This context, reflected in Laozi, Zhuangzi, and the other early philosophers, nonetheless indicates what Schwartz calls “highly mystical dimensions,” a viewpoint that implies the disparity between academic studies and esoteric practices.

According to Zhuangzi, “There is but one qi all under the heaven.”[11] “When man is born, his qi is gathered. When his qi is gathered, his life thrives. When his qi is dispersed, his life dies out.”[12] Graham observes that Zhuangzi “conceives training for the Way as the refining of the energizing fluids, the qi, by controlling one's posture and breathing.”[13] Zhuangzi specifies such training: “The True Man's food is plain, but his breathing is unfathomable and tranquil. While the breathing of the masses is through their throats, the breathing of the True Man is through his heels.”[14]

Apparently, the notion of “breathing through the heels” implies, or reveals, the Taoist “unfathomable and tranquil” breathing technique. This technique is supposed to dissolves the break point of inhalation and exhalation. The breathing becomes so tranquil and subtle that the entire body is permeated with the fused breathing, as if one breathes through the “heels instead of the throat (nose or mouth).” The great alchemist Ge Hong 葛洪 (283-363) was one of the first Taoist masters who reveled and defined this technique as taixi 胎息, or “fetus breathing”: “There are several ways to circulate qi… but the great essential is the fetus breathing. When one has attained the fetus breathing, one can breathe other than nose and mouth.”[15] Likewise, the view of the subject is also reflected in Laozi: “In concentrating one's qi and bringing it to the utmost degree of pliancy, can one become an infant?”[16] And, “one who receives the fullness of the Way can be compared to an infant (chizi 赤子). Wasps and scorpions do not sting him, nor snakes bite him, nor fierce beasts seize him, nor clawing birds maul him. His bones are supple, sinews are soft, but he grips firmly (wogu) 握固.”[17] Parallel with these lines, Ge Hong wrote: “When one is well cultivated in circulating qi, water will go up stream when one breathes out slowly; fire is extinguished when one breathes out slowly; fierce tigers and wolves submit when one breathes out slowly; scorpions and snakes coil when one breathes out slowly.”[18]

The terms “infant” and “grip firmly” should be treated with more attention. Rather than emphasize infancy, the stress should be laid on the “fetus,” or “fetus breathing.” According to the Inner Alchemic Classics, after ten months of “pregnancy with the fetus breathing,” the infant (chizi 赤子) is born. One then assiduously nourishes and cultivates the infant to grow up and become the True Man.[19] In other words, after practicing the subtle “fetus breathing,” one's “qi newborn” is formed in the body under the correct intent and consciously controlled breathing and body posture, which is called huohou 火候, or “the firing time.” One then continues to strengthen the “qi newborn” to reach adulthood—enlightenment—becoming the True Man.

On the other hand, the term of wogu, which deserves a new assessment, has been traditionally commented upon in Chinese texts as “grip firmly,” and so has it been translated in every English version of the Tao Te Ching. In fact, wogu might have meant more than it appeared literarily. Wogu is frequently used in the Taoist Classics and other traditional meditation literature as a “hand-crossed and thumbs-jointed” position for the posture of breathing. Joined with many others, Tao Hongjing 陶弘景 (456-536) consistently stated that one should “close the eyes and wogu (cross the hands with thumbs jointed before meditation).”[20]

It is sensible to assess Laozi's text as technical advice here: “Empty the heart, fill the abdomen,”[21] “extend farthest towards the void, hold steadiest to the tranquility. The ten thousand things all rise together, and I reflect their return.”[22] This “technique” is also clarified in Zhuangzi: “Unify your attention. Rather than listen with the ear, listen with the heart. Rather than listen with the heart, listen with the qi. Listening stops at the ear, the heart stills at following the circumstances. Qi is void, thus it is all encompassing. Only the Way amasses the void, so the void is the fasting of the heart.”[23] Both Taoists and Confucians consider the “fasting of the heart” (xinzhai心齋) one of the actual meditation techniques. By deepening and stilling the breath, one fasts the heart (empties mind/heart) of the thought normally accepted as its function as an organ, and waits for the perfectly attenuated fluid (qi) to respond and move in one direction or the other.

Philosophically, Laozi describes qi as the primal energy underlying all matter: “The ten thousand things bearing yin, yet embracing yang, unify a harmony through the fusing of qi,”[24] which is echoed by Zhuangzi: “The universe exhales its qi, and it is named wind.”[25] The statement attests to Bernhard Karlgren's glossary definition of qi as “vital principle,” which, however, should be considered in the thought of the Chinese cosmological scheme—the unity and continuity of time and space. For instance, the early medical text, Huangdi neijing 《黃帝內經》or the Yellow Emperor's Inner Book, traces the origins of human energy to the wind: “The east gives birth to the wind, the wind gives birth to the wood (agent), the wood (agent) gives birth to the sour flavor, the sour flavor gives birth to the liver, the liver gives birth to the tendon, tendon gives birth to heart.”[26] According to Confucius, qi is the source of emotional behavior: “In youth, one's blood and qi are not yet settled, one guards against lust. Having reached maturity, one's blood and qi is firm, one guards against aggressiveness. Having reached old age, one's blood and qi are in decline, one guards against avarice.”[27] Similarly, Mencius writes: “Hold fast to your will and do not violate your qi.” Thus, Mencius speaks: “I cultivate my primordial qi.”[28]

Mark E. Lewis observes: “Winds (qi) that pass through rich furnishings and comfortable lives carry cool refreshment, while winds that pass through filth and scenes of desperation make men ill. These ideas were later systematically developed into the Chinese theory of environmental influence known as ‘wind and water’ (feng shui) 風水.”[29] In addition, the early textual sources linked “wind” with “music.” Human music is a form of controlled or artificial wind, and wind a form of natural music; each could directly influence the other.

Likewise, the phrase “ode articulates what is intently on the mind, or poem articulates ambition 詩言志” from the Book of Shang《尚書》has been one of the greatest subjects in the Chinese intellectual and cultural history. Li Zehou contends that “ode” meant the magical incantations uttered by shamans in the earliest time. The relationship between the “ode” and the “music” in the traditional Chinese view was closely tied to the shamanistic rituals. "Ode" evolved from “shamanistic incantations” to documentation, eulogy, and the transmissions of ancestor worship, clan histories, and rituals and ceremonies.[30] Rao Zongyi argues that zhi 志, or the “mind or ambition,” speaks for “matter or event” and it also documents or records; however, the “ode” is a different way to document or record the “mind or ambition,” which should be viewed and conferred with qi. “Qi” is governed by the manifestation of things and events, and “mind, or ambition” is governed by heart/mind.[31]

A shaman’s magical incantations express his intention to transfer “mind or ambition” into the “qi,” which is a recognized form of an energetic substrate of matter. If “what is intently on the mind” is articulated as the movement of substance “qi,” this may be the original meaning of the phrase “ode articulates what is intently on the mind, or poems articulate ambition.” As Lewis observes, the “psychological-expressive element begins with a reformulation of the phrase ‘odes articulate aims/ambitions.’ The new formulation states that ‘odes are that into which the aims/ambitions go.’ As Stephen Owen has noted, this yields a spatialized theory of poetic production in which substance is transferred from inside to outside. It makes poetry part of a broader complex of theories of psychology as the movement of substance, in the form of the energetic substrate of matter.”[32] Edward Shaughnessy remarks that in Mencius “the terms zhi and qi are related in terms quite similar to those in this passage: The will is the leader of the vapor; the vapor is the filler of the body…. As vapor, it reaches greatness and reaches hardness, so that by directly nurturing it without harm then it will plug the interstice between heaven and earth.”[33]

Zhuangzi thus speaks: “the universe exhales its qi and it is named wind… then the pipes of the earth are those massed aperture, and the pipes of men are bamboo placed together.”[34] The concept of qi then is the primordial stuff underlying all matter, molded as cloud vapor and breath. It gives life to living beings. Qi gives us vitality, and the vital energy of the heart/mind, which controls our thoughts and emotions, moral sensibilities, and our body and physical activities.

[1] Graham, A. C., Disputers of the Tao, Philosophical Argument in Ancient China (Chicago: Open Court, 2003), 101.

[2] Schwartz, Benjamin I., The World of Thought in Ancient China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 181.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 182.

[5] John Lagerwey, “The Oral and the Written in Chinese and Western Religion,” in Gert Naundorf, Karl Heinz-Pohl, and Hans-Hermann Schmidt, eds. Religion und Philosophie in Ostasien: Festschrift für Hans Steininger zum 65 (Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann, 1985), 306-307.

[6] “Comme l’a bien démontré Jacques Derrida, notre civilisation du Livre est en réalité une civilisation de la Parole. Ce serait le fait d’utiliser une écriture phonétique qui nous aurait conduit à voir dans l’écriture un simple dédoublement de la ‘vive voix’: la parole seule—qu’elle soit de l’homme ou de Dieu—pouvait créer une chose, ou en rendre compte; elle seule pouvait exprimer l’essentiel—l’intention, la volonté—et elle était donc tout naturellement identifiée à ce qui fait vivre, à l’esprit, à l’âme, au soufflé. ‘L’ecriture,’ écrit Derrida, ‘la lettre, l’inscription sensible ont toujours été considérées comme le corps, la matière, extérieure à l’âme, au soufflé, au verbe et au logos.’ On ne pouvait, dans cette perspective, concevoir une écriture qui soit autre chose qu’une notation de la parole, qui soit même éternellement antérieure à la parole.

En Chine, cette écriture-là a toujours existé. Et, chose étonnante, elle était tout autant liée à la notion de souffle que l’idée que nous nous faisons de la parole. Pour nous, le lien entre parole et souffle va de soi. Quoi de plus naturel, en effet, que de réunir en un seul movement de la pensée la voix et le souffle “qui la porte: la parole, c’est le souffle qui appelle à l’existence, qui dénomme, découpe, distingue—en un mot, crée. L’expression ultime de ce parti pris occidental, c’est le Nom de Dieu.

Le cas de la Chine nous permet de comprendre que ce point de vue est le reflet de notre anthropocentrisme: c’est l’usage que font les humaines du souffle—pour parler—qui devient le modèle ontologique pour l’univers tout entier. En Chine, c’est le souffle tout court qui compte: dans le tohu-bohu—que les Chinois dénomment hun-tun, Humpty-Dumpty—de l’origine, le souffle circule, d’abord informe, chaotique, puis, après de longs cycles de gestation, prend forme, ou plutôt se décante. Les souffles purs et légers montent pour faire le ciel, les souffles troubles et lourds descendent pour faire la terre. Dès lors, l’univers—univers qui se dit tiandi, ‘ciel-terre’: ‘di-vers’—existe.” Lagerwey, “Écriture et corps divin en Chine” in Le Corps des dieux, vol. 7 of Le temps de la réflexion, edited by Charles Malamoud and Jean-Pierre Vernant (Paris: Gallimard, 1986), 275-276.

[7] Liu Wendian, 劉文典, Commentaries on Prince Huainan淮南鸿烈集解 (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1989), 172.

[8] Schwartz, The World of Thought in Ancient China, 180.

[9] Sarah Allan, The Way of Water and Sprouts of Virtue (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 88.

[10] Li Ling 李零, A Study on Chinese Occult Arts 中國方術考 (Beijing: Eastern Press, 2001), 345.

[11] Guo Qingpan 郭慶藩, An Elucidation on Zhuangzi 莊子集釋 (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1997) 737.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Graham, Disputers of the Tao, 188.

[14] Ibid., 288.

[15] Wang Ming 王明, Clarification on the Inner Chapters of Baopu zi 保朴子內篇校釋 (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1996), 149.

[16] Gao Ming 高明, Commentaries on the Silk Scroll Book of Laozi 帛書老子校註 (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1996), 262.

[17] Ibid., 89-93.

[18] Wang Ming, Clarification on the Inner Chapters of Baopu, 150.

[19] “The Imperative Doctrines for Human Nature and Longevity 性命圭旨" in Fang Chunyang 方春陽 ed. Zhongguo Qigong Dacheng 中國氣功大成 (Changchun: Jilin Kexuechubanshe, 1999), 783.

[20] "Records Concerning Tending Life and the Prolonging of Life 養性延命錄" in Zhongguo Qigong Dacheng, 783.

[21] Gao Ming, Commentaries on the Silk Scroll Book of Laozi, 273.

[22] Ibid., 298.

[23] Guo Qingpan, An Elucidation on Zhuangzi, 147.

[24] Gao Ming, Commentaries on the Silk Scroll Book of Laozi, 29.

[25] Guo Qingpan, An Elucidation on Zhuangzi, 45.

[26] Meng Jingchun 孟景春, Explication on the Yellow Emperor's Inner Book, the Original Questions 黃帝內經素問譯釋 (Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 1996), 44.

[27] The Analects, in Commentaries on the Thirteen Classics 十三經註疏 (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1979), 2522.

[28] Ibid., 2685.

[29] Mark Edward Lewis, Sanctioned Violence in Early China (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 218.

[30] Li Zehou 李澤厚, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy (New York: The Free Press, 1966), 43.

[31] Rao Zongyi 饒宗頤, "Re-treaty on Odes Articulate What is Intently on the Mind: Based on the Guodian Materials," 88.

[32] Mark Edward Lewis, Writing and Authority in Early China (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 174.

[33] Edward Shaughnessy, Rewriting Early Chinese Texts (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 49.

[34] Guo Qingpan, An Elucidation on Zhuangzi, 49.